Each spring for more than two decades, Anita Fahrni-Minear has returned to Mongolia not as a tourist, but as a friend, mentor, and quiet force for educational transformation.

“It’s very nice to be here again,” Anita shared warmly during our conversation at the ACMS office in Ulaanbaatar. “I’ve been coming every year since 1998, except during COVID. This country and its people have become such a big part of my life.”

Her contributions span from launching educational exchanges to writing bilingual storybooks that now reach thousands of young Mongolians each year. What began as a personal commitment has grown into a powerful legacy of language, storytelling, and opportunity.

Bridging two nations through student exchange

In the early 2000s, Anita helped launch what became Mongolia’s first large-scale student exchange with Switzerland. Since then, more than 120 Mongolian students, primarily young women studying German, have spent an academic year living and studying in Switzerland. Many are now teaching in public schools across the country.

“They live with host families, study in teacher-training colleges or high schools, and return with a deeper understanding of language and education,” Anita explained. “That experience continues to shape their careers and classrooms back home.”

She also coordinated the arrival of more than 160 volunteer teachers from Switzerland, Germany, and the United States to Mongolia. These volunteers, placed in both urban and rural schools, teach English and German while introducing interactive, student-centered methods.

“It takes a lot of planning,” Anita admitted, “but seeing students come alive in the classroom makes it all worth it.”

Books written for and about young Mongolians

Noticing a lack of accessible, age-appropriate English materials for Mongolian students, Anita began writing bilingual English–Mongolian storybooks. Each book is printed in 10,000 copies, published locally, and distributed free of charge to schools and libraries across eight aimags.

“Young people want to read stories they can relate to,” she said. “So I write about characters based on real situations, like bullying, corruption, moving to a new town, or environmental concerns.”

Her first book, Tuya’s Trip, follows a young girl visiting the Great Gobi B Reserve and learning about conservation. Inspired by Anita’s service on the board of the International Takhi Group, the story reflects her passion for Mongolia’s wildlife and environmental education.

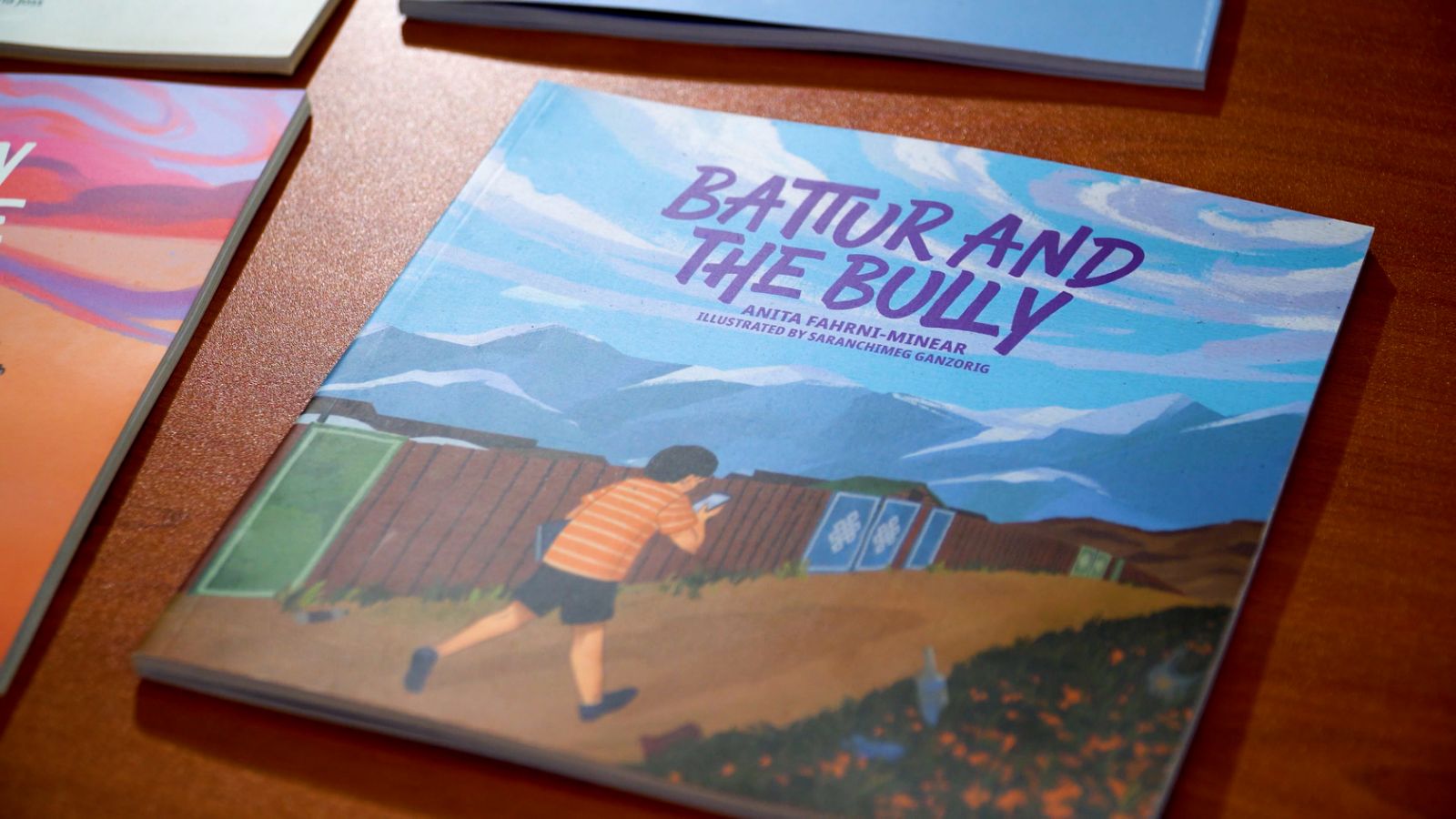

Subsequent titles like Munkhsuld’s Move,and Battur and the Bully tackle real social issues including peer pressure, inclusion, domestic violence, and Mongolia’s turbulent transition after the Soviet era.

Each story includes a Mongolian translation in the back so families and students at all levels can read together. “Even if the parents don’t speak English, they can still understand and discuss the story with their children,” Anita said.

Reading as a habit and a lifelong skill

Anita emphasizes that developing a reading habit early is essential—not just for language learning, but for personal growth.

“There was a study in Ulaanbaatar showing that few parents read to their children. That’s a problem,” she noted. “Children who read, and who are read to, perform better in school and think more critically.”

Her bilingual books are now used in classrooms across the country, especially in places where access to books is limited. “Some students told me these are the first books they’ve ever owned in English,” she shared.

Beyond language skills, Anita’s stories also help young people reflect on important and sensitive topics.

“I’m really pleased that I can keep writing, and that the books are being used by both younger students and 12th graders,” she said. “One of my stories is about domestic violence, which is a problem everywhere, not just in Mongolia. I was very glad to hear that it was discussed by many older students.”

She explained that many of the topics she writes about bullying, inequality, corruption, or environmental problems—are things people experience but rarely talk about. “When you put those stories on paper, they become easier to think about and easier to discuss.

Why education is the foundation of development

For Anita, the strength of a society lies in how well its people are educated. Education, she believes, goes beyond formal instruction. It’s about teaching people to think for themselves, to question what they see, and to respond thoughtfully to both challenges and opportunities.

“If people are well educated, they can work toward improvements themselves,” she said. “Money matters, of course, but basic education is far more important for learning to think independently, not just doing what everyone else does.”

She believes every community, whether in a developing or developed country, has room for improvement. “Everyone can contribute to change. But those with better education are often better equipped to think deeply, evaluate clearly, and take meaningful action.”

Investing in rural youth and young women

Anita’s exchange and book programs have intentionally focused on rural and marginalized communities. “Students from remote aimags often have fewer chances to go abroad or experience new ideas,” she said. “So I tried to focus there.”

Many of her alumni are now teachers in rural schools. Others work in translation, tourism, or NGOs—equipped not just with stronger language skills, but with a broader worldview. “I’ve seen firsthand how one year abroad or one good book can open someone’s mind,” she said.

A witness and storyteller of Mongolia’s transformation

Anita first arrived in Mongolia shortly after the 1998 assassination of democracy leader Zorig Sanjaasuren. Over the decades, she has witnessed the country undergo profound transformation.

“Back then, the store was empty. There was little infrastructure,” she recalled. “Today, there are supermarkets, coffee shop, and people with option and optimism. But we shouldn’t forget how far it has come.”

At the same time, she acknowledged that frequent change in government and leadership continues to pose challenges. “Continuity is a challenge,” she said. “Project need consistency.” Yet despite these hurdles, Anita remains committed to her work—and to Mongolia. Writing has become her way of both contributing to and learning from the country’s evolving story.

“Writing helps me keep learning about Mongolia,” she said. “Each time I visit, I talk with people, take note, and base my story on those conversation. The character are fictional, but the situation are very real.”

Legacy of quiet leadership

As our conversation drew to a close, I asked Anita what drives her to continue. Her answer was humble and heartfelt.

“I’m in a very privileged position to do this work, and I’ve learned just as much as I’ve given. It’s a give and take. Mongolia has enriched my life.” With friends across the country and inspiration flowing through every conversation and classroom visit, Anita shows no sign of slowing down. “I’ll keep writing and traveling as long as I can,” she said. “We’ll see what comes next.”